We interact with nutrition labels nearly every time we visit the grocery store. For many of us, they still feel confusing, misleading, or even irrelevant. In fact, a 2018 study found that nearly 98% of consumers didn’t fully understand how to read nutrition labels. It’s not a personal failing—it’s a reflection of how the system is built.

Do nutrition labels really have to be this complicated?

Nutrition labels were designed to inform, yet they often overwhelm. Some of that confusion is by design — because when clarity favors consumers, it doesn’t always benefit big food companies. But with a little education and curiosity, we can understand how to read nutrition labels. We can reclaim the information as a helpful tool rather than a source of stress.

This guide is here to simplify, not to scare. It should help you feel more confident about how to read nutrition labels and make food choices that feel good for you! The information here reflects nutrition label guidelines as of December 2024, and labels may evolve over time. However, much of what you’ll learn is evergreen and nourishing for both the body and the mind.

An Overview of How to Read Nutrition Labels

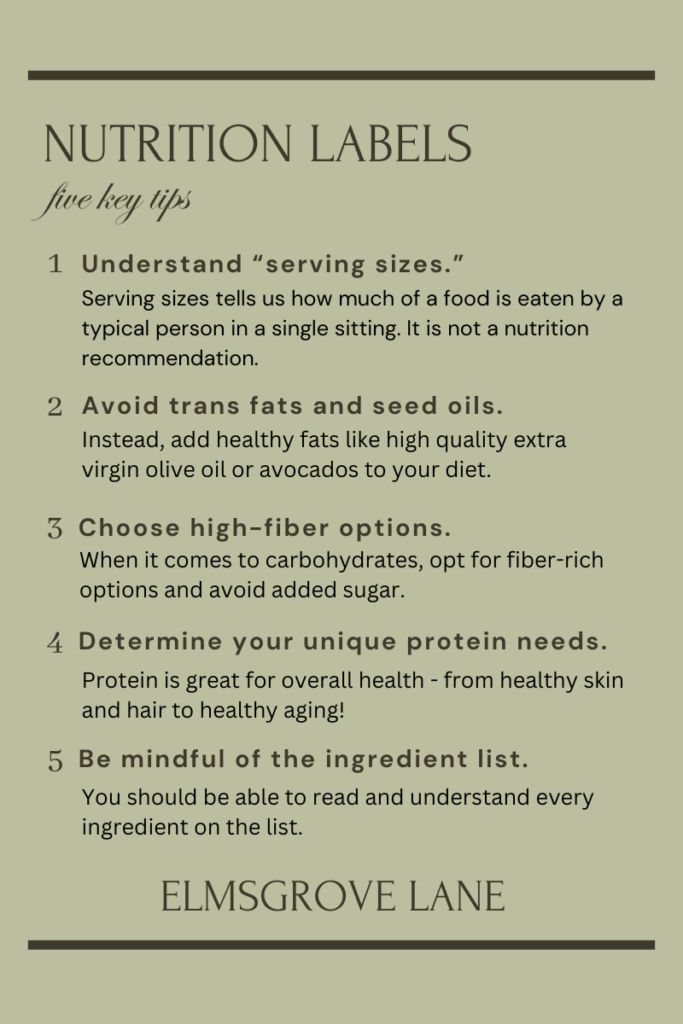

- Serving Size – This number isn’t a recommendation—it’s a reflection of what people typically eat in a sitting. Most serving sizes are smaller than what we actually consume, which affects every other value on the label.

- Calories – Pay attention to how much you’re truly eating. Calories listed are per serving, not per package. Do a little math to get an accurate picture.

- % Daily Value – This shows how much a nutrient contributes to a standard 2,000 calorie diet. It’s a helpful guide, but not a personalized one—everyone’s needs vary.

- Fat – Don’t fear fat—quality matters more than quantity. Look for high quality fats and avoid trans fats and highly processed seed oils.

- Cholesterol – The number on the label matters less than the quality of your overall diet. Focus on real, whole foods instead of obsessing over numbers.

- Sodium – Sodium isn’t the enemy, but excess in ultra-processed foods can add up quickly. Whole or home-cooked foods give you more control.

- Carbohydrates – Fiber is your friend. Prioritize whole grains, beans, and unrefined carbs. Keep an eye out for added sugars (especially where you least expect them)!

- Protein – Look at grams — not just the %DV — and aim to get enough protein based on your own needs.

- Vitamins – Labels only show a few nutrients. A real food–focused diet is still the most reliable way to get what your body needs.

- Ingredient List – Shorter is better. Aim for recognizable, whole ingredients. Watch out for trans fats, seed oils, gums, artificial sweeteners, and vague terms like “natural flavors.”

Bottom line? Labels are tools—but they’re not always telling the whole story. Let them inform you, not confuse you. And remember: the most nourishing foods don’t come with a label – they come from the Earth.

A Short History of How to Read Nutrition Labels (And Why They’re Still So Misunderstood)

In 1990, the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) gave the FDA the authority to require nutrition labeling on packaged foods. At the time, Dr. Louis W. Sullivan, then Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services, was a leader in the charge to revise the food label. In appeals leading to the change, in 1990 he stated that “the grocery store has become a Tower of Babel and consumers need to be linguists, scientists and mind readers to understand the many labels they see.”

The FDA does not create nutrition labels for packaged foods we see on shelves in our grocery stores. The FDA regulates nutrition labels that food manufacturers produce. This gives corporations ample opportunity to transform what should be a factual nutrition label into a marketing appeal through false claims and massaging key indicators like “serving size.” In fact, class-action lawsuits alleging misinformation on food labels have been on the rise since 2019.

We must be intelligent consumers and deduce real information from the “facts” we are provided. Not all consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies intend to mislead. However, the FDA nutrition label guidelines, intended for the layperson, are themselves misleading without education on their true meaning.

How to Read Nutrition Labels: Components Breakdown

Serving Size: Why It Matters More Than You Think

Serving size tells us how much of a food is eaten by a typical person in a single sitting. Serving size, per the FDA, is not a fact-based recommendation of how much food the typical person should eat. This number affects nearly every other piece of data on the label.

This number is often inaccurate, underestimating the amount that a typical person eats in a single sitting. Let’s be honest – does anyone really eat just 12 chips in a single sitting?

It is also important to recognize that a serving size may not be the same as a package size. A single package may have multiple servings. A strength of the FDA-regulated nutrition label, serving size is specified on packaged foods, and in 2020 was given a bold, increased font size to add visibility to the amount of food in a package.

Calories: Understanding What You’re Really Eating

Because serving sizes on packaged items are often underestimated, you could be consuming more calories than you think.

For a true read on calories consumed, consider how much of a product you are actually eating in a single sitting, and do some math to achieve accurate numbers based on true consumption. For example, if you are eating 30 of these chips in a sitting, you’d need to multiply all other values by 2.5 for accurate calories and amounts consumed.

% Daily Value: A Misleading Metric Without Context

Like calories, keep in mind that % Daily Value is based on the 2000 calorie/day diet as specified on nutrition labels.

While Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) specifies the amount of a nutrient required to meet the needs of most healthy people, % Daily Value is simply a percentage of the RDA based on how much of the nutrient exists in a single serving. Again, “serving” is specified by food manufacturers and is often underestimated.

For an understanding deeper than how to read nutrition labels, consider talking with a dietician or health professional.

Fats: The Good, The Bad, and the Ultra-Processed

Fat is calorie-dense, so in general the higher the fat content, the more calories a food product will have. Fat often gets a bad name, however high quality fats (both saturated and unsaturated) are a critical component of a healthy diet and can promote blood sugar regulation.

Trans fats and seed oils should be limited or altogether avoided. See “ingredients list” to learn more about these fats and how to identify if they are in your products.

Cholesterol: Focusing on Food Quality Over Numbers

Current USDA Dietary guidelines leave room for flexibility when it comes to cholesterol. Instead of focusing too much on the % daily value of cholesterol you see listed on nutrition labels, try to focus on adding real, whole foods (including plant-based options typically known to have lower cholesterol) into your diet.

Sodium: Know Your Numbers, But Don’t Fear Salt

Sodium attracts water into cells and is key for staying hydrated.

With more trendy electrolyte powders on the market than ever before, there’s an ongoing debate in health and nutrition as to how much sodium is really needed. One thing that is not up for debate is that sodium requirements can be influenced by your level of activity and how much you sweat.

In general, do not be afraid of sodium, but be mindful of exorbitant amounts on food labels. Many ultra- processed foods have extremely high levels of sodium, like canned soups or vegetables. Instead try cooking fresh or to save time, frozen vegetables, and add sodium to whole foods in the cooking processes.

Carbohydrates: Fiber, Sugar, and What to Watch Out For

Carbohydrates can tend to have a bad reputation, but they are critical to our health because they are the primary source of energy in the human diet. Some carbohydrates are superior to others. Carbohydrates are broken down to three sections on the nutrition label:

- Fiber is considered an important part of a healthy diet. A high fiber diet can promote a healthy digestive system and blood sugar levels, amongst many other benefits. Opt for high fiber products when possible, specifically unrefined options like whole grains, beans, and nuts.

- The sugar section on the label includes both naturally occurring and added/artificial sugar. As a general rule, the lower the sugar intake, the better. More so than this section, keep an eye on the “Added Sugar” numbers.

- Added Sugar is one of my biggest concerns when it comes to reading nutrition labels, because so much sugar is added to products that just don’t need it. From pasta sauces to salad dressings and beyond, sugar hides in most of the packaged foods you find on shelves. The CDC sites sugar as a concern in the American diet and recommends limiting added sugars in your diet. Personally, I opt only for naturally occurring sugars (like fruit, and some raw honey or pure maple syrup on occasion) in my own diet.

Protein: How Much Do You Actually Need?

Based on a 2000 calorie diet, the FDA recommends 50g of protein per day, however the Recommended Dietary Allowance for protein is .8g per pound of bodyweight. Many times, following the RDA would far exceed the FDA recommendation.

Protein has many benefits, from strengthening hair, skin, and nails to promoting stronger bones and healthy aging. In my own diet, I aim for .8-1g of protein per pound (or at least 100g per day) and achieve this by trying to consume 25-30g of protein at each meal and one high-protein snack.

One of my favorite protein-focused snacks is plain Greek yogurt with nuts and fruit. About one cup of yogurt plus 1/4 cup cashews (as shown in the photo above) has a little over 26 grams of protein and 310 calories, making it a nutritious and filling snack to support protein goals. I skip any sweetener and instead add a little fresh fruit for extra nutrients. Here, I added kiwi, which has lots of immunity-boosting Vitamin C and fiber to support healthy digestion.

Consider calculating protein needs for your unique body according to the RDA by multiplying your weight x 0.8 grams. This will give you a reference point for your body’s protein needs based on the RDA. Then, reference the total grams of protein on the packaged foods instead of the % daily value to better reach your protein goals.

Vitamins & Minerals

The vitamins section on nutrition labels is limited and contains a small number of vitamins and minerals that have been deemed as lacking in the American diet. Instead of giving too much focus to this section of the label, consider choosing real, whole foods for a nutrient-dense diet instead. If you are interested in supplementing your diet or concerned about personal nutrient deficiencies which may differ per person and life situation, I recommend speaking with a dietician or health professional.

Ingredient List & Clean Labels

The healthiest foods don’t come in a package, but the best packaged foods have the shortest ingredient lists. Products with fewer ingredients listed on the label are less likely to be ultra processed, like canned beans.

The ingredients are organized in descending order by weight, meaning that the most prominent ingredients are listed at the top. If you do not recognize the names of any of the ingredients on the list, particularly the top three or four, beware and reconsider the product.

Ingredients to Avoid: Trans Fats, Seed Oils, and “Natural Flavors”

To learn more about ingredient lists and ultra-processed foods, I highly recommend Ultra-Processed People by Chris Van Tulleken. Everyone is different – I encourage you to determine for yourself what is acceptable in your own diet. Here are a few ingredients I watch out for and avoid altogether:

- Do not consume any product with the word “hydrogenated” on the label, which indicate trans fats banned in other countries and linked to chronic disease.

- Seed Oils include canola, corn, soy, sunflower, and safflower oil, amongst others that I see less frequently on nutrition labels. Seed oils are ultra-processed with extreme heat, causing oxidation and byproducts which can contribute to inflammation. Read more about seed oils here.

- Gums, or thickening agents that can contribute to digestive issues like guar gum, xanthan gum, and carrageenan. Eliminating gums from my diet has greatly helped with my own overall health and digestion – I physically feel a difference having made this dietary change.

- While sugars should be avoided on packaged foods, artificial sweeteners have also been linked to digestive issues and keep you hungry. Watch out for aspartame, Splenda, and sugar alcohols (pro tip: avoid products with words ending in “-ol” like xylitol, which is a sugar alcohol).

- Natural Flavors, which aren’t really all that natural. The term “natural flavors” does not mean that the ingredients are natural, but instead that ingredients are derived from natural elements, indicating that natural flavors can (and usually are) highly processed. Read more about the FDA’s definition of natural flavors here.

Closing Empowerment

The Healthiest Foods Don’t Have Labels — But You Can Still Be a Smart Consumer

The healthiest foods aren’t made in factories – they are grown from the earth and on farms, with a farmer’s hard work and dedication. I hope you feel empowered to make more educated purchasing decisions, so that together we can create healthier lives and a healthier country.

→

JOIN THE LIST

Subscribe to Today's Harvest by Elmsgrove Lane on Substack.